|

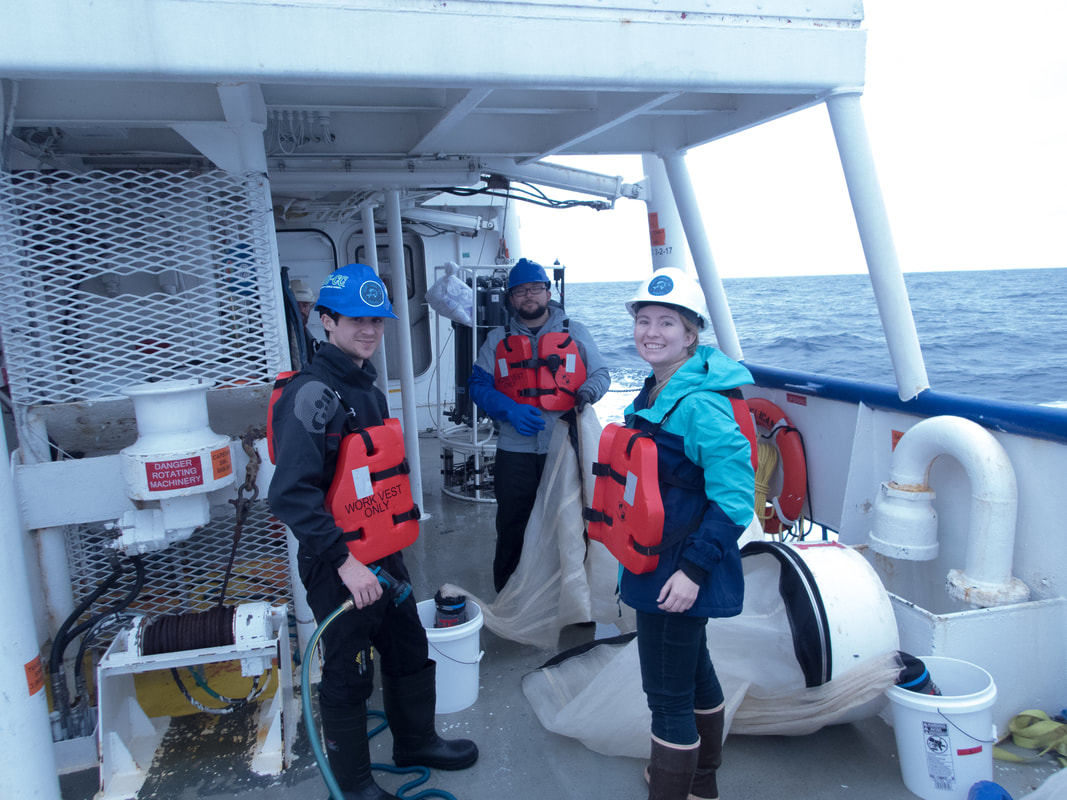

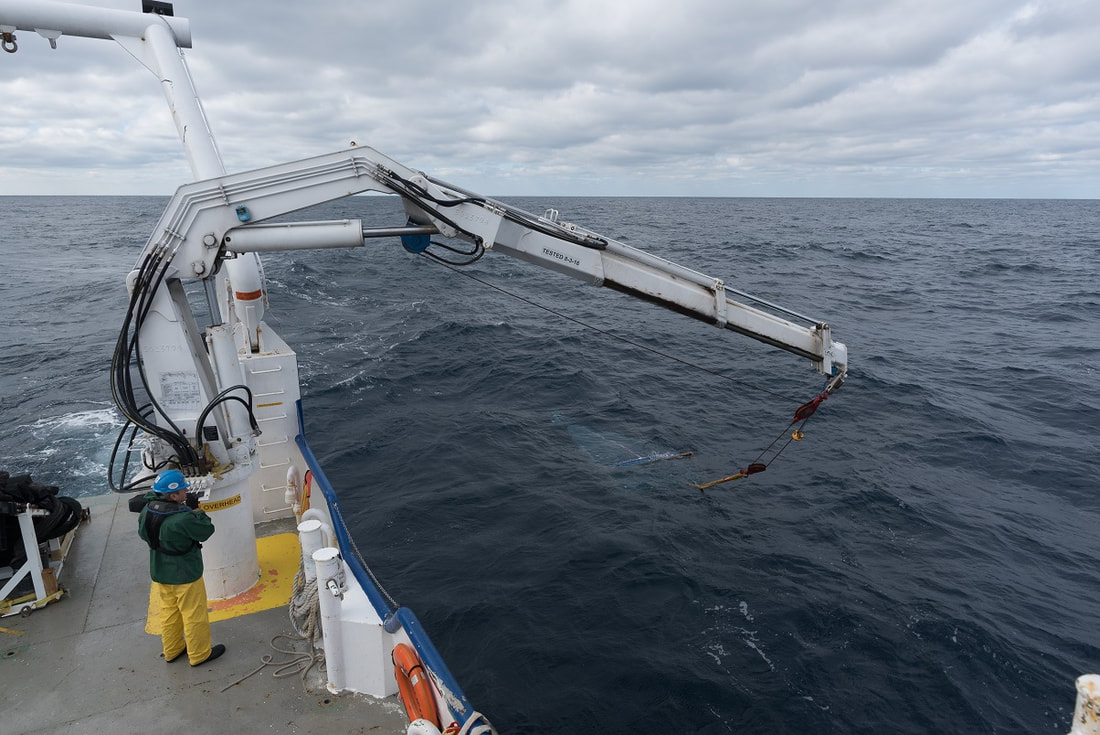

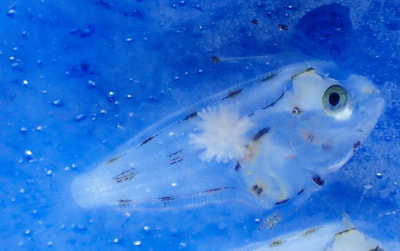

Posted by Dr. Simon Geist, Department of Life Sciences, Texas A&M Corpus Christi We are already at the last full sampling day of our second NSF RAPID Plankton cruise in the Gulf of Mexico waters off Galveston. Time is going by fast, especially since we got on board Sunday afternoon, so we have to hurry to get this blog post out while still at sea! Last Sunday morning, we started from Corpus Christi to meet our research vessel for this cruise, the R/V Pelican at the dock in Galveston. Our truck was so packed with sampling gear and jars, microscope and personal luggage, that Daniel Hardin and Cristian Camacho, two undergraduate researchers in our lab, had to follow in a second car, since they did not fit in the truck anymore. After a 5 hour drive and getting some last supplies on the way, we arrived in Galveston where we met Gabrielle Corradino and Aubree Szczepanski from the Schnetzer lab at NCSU. Around 3 p.m. the Pelican, with our Cajun colleagues from the Stauffer and Robinson labs at ULL already onboard, arrived at the dock and we and our equipment got aboard very smoothly. Since then, we have sampled 8 stations from very nearshore to more than 1,000 m deep offshore during the last days and are on-track to complete the last 2 stations by tomorrow early morning. Our days onboard start at 6 a.m. with a short breakfast, before the first net is deployed in the water around 6:45-7:00 a.m. At each sampling station, an array of plankton nets, as well as a CTD (to record depth profiles of temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and chlorophyll a) and a rosette water sampler are deployed so it takes us about 3 hours to complete a station until we can steam to the next station.  Graduate student Shannan McAskill labels sampling jars in preparation for the next station Graduate student Shannan McAskill labels sampling jars in preparation for the next station So why are we here? Our group is interested in how changing environmental conditions affect the occurrence, health and survival of larval fish. These fish babies are only a few days or weeks old and very tiny (few millimeters to centimeters) so that you have to look very carefully to detect them. This little size means that they are not very strong swimmers yet and cannot choose to leave the body of water in which their parents spawned. So these tiny fish larvae have to cope with the environmental conditions (temperature, salinity, etc.) they meet and hope that there is also enough energy-rich food of the right size available to allow them to grow up fast. Hurricane Harvey caused a record amount of rainfall and, with it, freshwater discharge into the coastal Gulf of Mexico off Galveston during a time of the year in which it usually does not rain very much. This freshwater has a lower salinity than seawater, which makes it lighter (at the same temperature) and allows it to create a surface layer of fresh water on top of the seawater. Colleagues from Galveston observed this huge freshwater “blob” more than a month after the Hurricane hit the coast in the middle of last October. In addition to the freshwater, a lot of nutrients were washed into the Gulf as well. These nutrients stimulate phytoplankton growth and may have caused a change in abundance, biomass and species composition of zooplankton organisms. In our project, the groups of Beth Stauffer, Astrid Schnetzer and Kelly Robinson are looking at the immediate and mid-term effects of the Hurricane Harvey freshwater plume on phyto- and zooplankton composition and food web interactions. These different timescales are needed since the freshwater will be mixed with seawater by winds and currents rather quickly, whereas the effects of the additional nutrient inflow may prevail for several months. This unusual environmental conditions may have affected larval fish in different ways: those that were born right after Hurricane Harvey had to cope with lower salinities than usual and most likely with a changed meal plan, and the ones born a couple of months later may still see this change in meal plan. It is possible that not all species can cope similarly well with such a changed environment, which could affect the number of adults of those species a few years later. Therefore, our group wants to understand if these unusual environmental conditions have an effect on the species composition of the larval fish community in the affected area, and for how long after the event this plays a role. For a subset of selected species, we will also look more details into their diet composition as well as into growth rates as indicator of larval health, and link our findings to the results from the other research groups in the project. Thanks to our great collaborators from the NOAA Ichthyoplankton lab in Pascagoula (Glenn Zapfe and his team) we will be able to compare our new samples collected after Hurricane Harvey with data from regular SEAMAP plankton monitoring cruises of previous years. To make it even better, Shannan McAskill, a PhD student in our group, was able to go out with the NOAA field team led by Pam Bond during the 2017 Fall monitoring cruise in the second half of September and collect samples 2-3 weeks after the event. And thanks to our own three RAPID cruises in October 2017, and January and March 2018 we are able to study the effect of the Hurricane Harvey flood plume on the Plankton community over several months. So what are we really doing onboard the research vessel all day? During our RAPID plankton cruises, four different net types are deployed at every sampling station, and each serves a different purpose. First, we use the two standard net types of the regular NOAA SEAMAP monitoring program. The BONGO consists of two, parallel round frames (looking like a Bongo drum) to which nets with a 335 μm mesh size are attached, which is a good size to catch smaller, recently hatched larvae. The NEUSTON consists of a large rectangular frame to which a 950 μm (almost 1 millimeter!) mesh is attached. This net is specially designed to catch larger and older larvae, which occur right at the ocean surface. The third net type is a simple RING net equipped with a 1 mm mesh. Along the with BONGO, the RING net samples the whole water column from the surface to close to the bottom.  Dr. Simon Geist concentrates a net tow sample in the wet lab Dr. Simon Geist concentrates a net tow sample in the wet lab The fourth net type is the most sophisticated one: the MOCNESS has a rectangular frame to which 10 nets of 333 μm mesh are attached, which are opened and closed one at a time. This allows us to target different discrete depths to detect if zooplankton and fish larvae are aggregating in a certain depth layers of the water column. It is important to get as close to the bottom, since some zooplankton and fish larvae may hide out very close to it during the day. We have an online depth sensor attached when these nets are deployed, which allows us to get very close to the bottom (within 2 m) without running the net aground, which would result in the damage or loss. Fingers crossed, but so far we have not lost any gear during the October and the January cruise. After a net is successfully recovered, the mesh needs to be rinsed down carefully to collect organisms that are sticking to the mesh into the so-called “cod end” or net bucket. We then gently transfer what we’ve collected into a sample jar, to which either pure ethanol or formalin solution as fixatives are added to preserve the organisms. We have encountered a nice variety of larval and juvenile fish so far, which will be identified back home in the lab. However, we are curious to hear your thoughts about which species are shown in the 13 images provided here. Let us know in the comments, on our Facebook site or via email to [email protected]! All in all, we keep ourselves busy during the days at sea and everybody is quite tired when going to bed in the evening. The constant rolling of the boat does its part as well, but we were lucky that the sea was not as rough as one could imagine for being the middle of winter. Over time, working on a research vessel can be quite exhausting and I think each of us is happy to have a holiday on Monday to recover. We are all really impressed how smoothly both of our cruises have gone. The atmosphere onboard both the R/V Point Sur and the Pelican have been fantastic, and I consider myself very lucky that our team consists of enthusiastic researchers and crew who get along with each other, especially considering that we’re all cramped together on a small vessel for a week.

So long, we are off to knock the last stations out for this cruise! After that, we will return home to Corpus Christi and get some samples analyzed until we come back for our third and last cruise of this project in March!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsMembers of the Stauffer Lab in the Dept. of Biology at UL Lafayette. Check out the byline for specific blog post author information! Archives

March 2018

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed