Grad students Andrea Jaegge (UL Lafayette) and Aubree Szczepanski (NC State Univ.) successfully set up a second grazing experiment on our first science day Grad students Andrea Jaegge (UL Lafayette) and Aubree Szczepanski (NC State Univ.) successfully set up a second grazing experiment on our first science day The third and final cruise for our NSF-funded RAPID project has departed from Galveston, TX, following a slight deviation from the original schedule. Read more about this cruise on our colleague's cruise blog here: https://cajunplankton.com/2018/03/19/rapid-3-chasing-sleep-wee-beasties/ We will also be tweeting from sea tomorrow, 20 March, between the hours of 8 am and 8 pm CDT. Find our Twitter feed (@bastauffer) to participate, or send in a question you'd like to ask about science or life at sea via email ([email protected]). Hope to "see" you there!

1 Comment

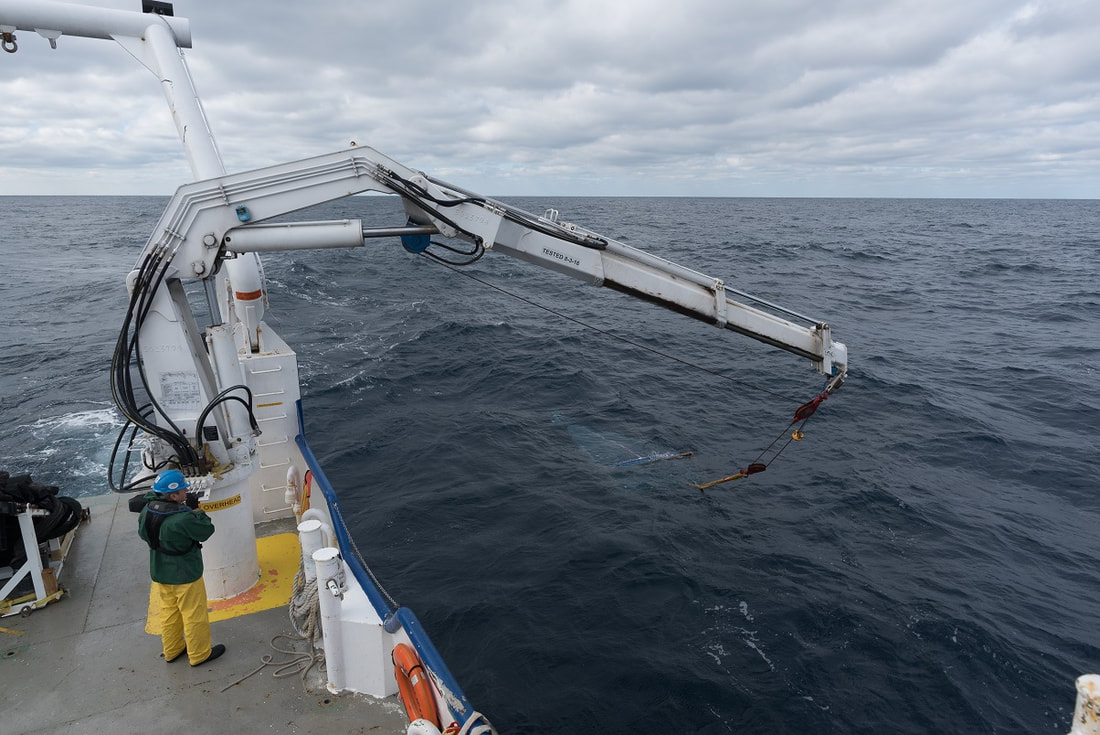

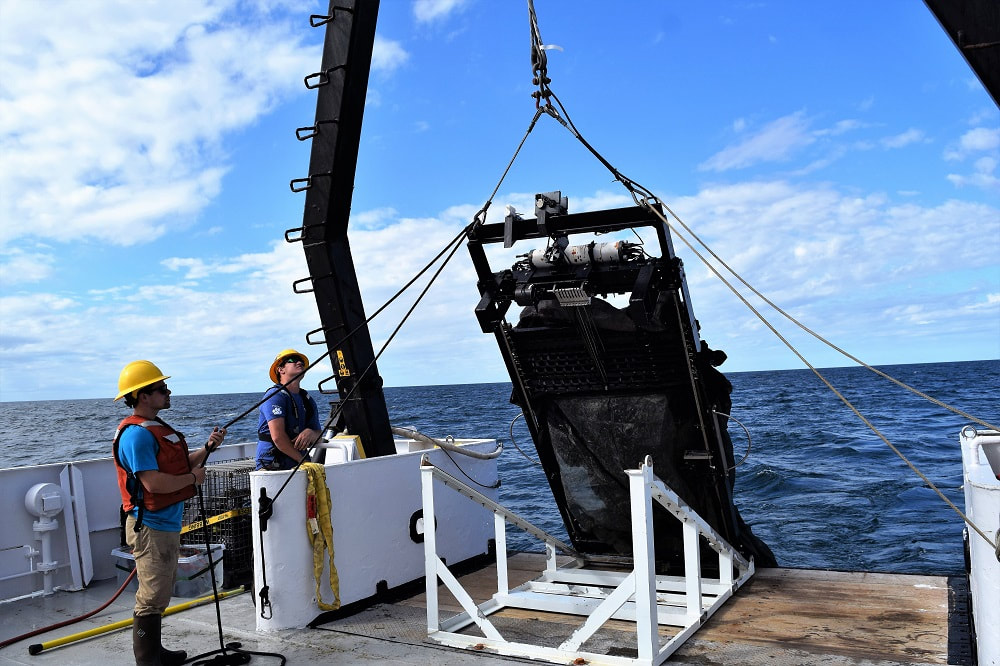

Posted by Dr. Simon Geist, Department of Life Sciences, Texas A&M Corpus Christi We are already at the last full sampling day of our second NSF RAPID Plankton cruise in the Gulf of Mexico waters off Galveston. Time is going by fast, especially since we got on board Sunday afternoon, so we have to hurry to get this blog post out while still at sea! Last Sunday morning, we started from Corpus Christi to meet our research vessel for this cruise, the R/V Pelican at the dock in Galveston. Our truck was so packed with sampling gear and jars, microscope and personal luggage, that Daniel Hardin and Cristian Camacho, two undergraduate researchers in our lab, had to follow in a second car, since they did not fit in the truck anymore. After a 5 hour drive and getting some last supplies on the way, we arrived in Galveston where we met Gabrielle Corradino and Aubree Szczepanski from the Schnetzer lab at NCSU. Around 3 p.m. the Pelican, with our Cajun colleagues from the Stauffer and Robinson labs at ULL already onboard, arrived at the dock and we and our equipment got aboard very smoothly. Since then, we have sampled 8 stations from very nearshore to more than 1,000 m deep offshore during the last days and are on-track to complete the last 2 stations by tomorrow early morning. Our days onboard start at 6 a.m. with a short breakfast, before the first net is deployed in the water around 6:45-7:00 a.m. At each sampling station, an array of plankton nets, as well as a CTD (to record depth profiles of temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and chlorophyll a) and a rosette water sampler are deployed so it takes us about 3 hours to complete a station until we can steam to the next station.  Graduate student Shannan McAskill labels sampling jars in preparation for the next station Graduate student Shannan McAskill labels sampling jars in preparation for the next station So why are we here? Our group is interested in how changing environmental conditions affect the occurrence, health and survival of larval fish. These fish babies are only a few days or weeks old and very tiny (few millimeters to centimeters) so that you have to look very carefully to detect them. This little size means that they are not very strong swimmers yet and cannot choose to leave the body of water in which their parents spawned. So these tiny fish larvae have to cope with the environmental conditions (temperature, salinity, etc.) they meet and hope that there is also enough energy-rich food of the right size available to allow them to grow up fast. Hurricane Harvey caused a record amount of rainfall and, with it, freshwater discharge into the coastal Gulf of Mexico off Galveston during a time of the year in which it usually does not rain very much. This freshwater has a lower salinity than seawater, which makes it lighter (at the same temperature) and allows it to create a surface layer of fresh water on top of the seawater. Colleagues from Galveston observed this huge freshwater “blob” more than a month after the Hurricane hit the coast in the middle of last October. In addition to the freshwater, a lot of nutrients were washed into the Gulf as well. These nutrients stimulate phytoplankton growth and may have caused a change in abundance, biomass and species composition of zooplankton organisms. In our project, the groups of Beth Stauffer, Astrid Schnetzer and Kelly Robinson are looking at the immediate and mid-term effects of the Hurricane Harvey freshwater plume on phyto- and zooplankton composition and food web interactions. These different timescales are needed since the freshwater will be mixed with seawater by winds and currents rather quickly, whereas the effects of the additional nutrient inflow may prevail for several months. This unusual environmental conditions may have affected larval fish in different ways: those that were born right after Hurricane Harvey had to cope with lower salinities than usual and most likely with a changed meal plan, and the ones born a couple of months later may still see this change in meal plan. It is possible that not all species can cope similarly well with such a changed environment, which could affect the number of adults of those species a few years later. Therefore, our group wants to understand if these unusual environmental conditions have an effect on the species composition of the larval fish community in the affected area, and for how long after the event this plays a role. For a subset of selected species, we will also look more details into their diet composition as well as into growth rates as indicator of larval health, and link our findings to the results from the other research groups in the project. Thanks to our great collaborators from the NOAA Ichthyoplankton lab in Pascagoula (Glenn Zapfe and his team) we will be able to compare our new samples collected after Hurricane Harvey with data from regular SEAMAP plankton monitoring cruises of previous years. To make it even better, Shannan McAskill, a PhD student in our group, was able to go out with the NOAA field team led by Pam Bond during the 2017 Fall monitoring cruise in the second half of September and collect samples 2-3 weeks after the event. And thanks to our own three RAPID cruises in October 2017, and January and March 2018 we are able to study the effect of the Hurricane Harvey flood plume on the Plankton community over several months. So what are we really doing onboard the research vessel all day? During our RAPID plankton cruises, four different net types are deployed at every sampling station, and each serves a different purpose. First, we use the two standard net types of the regular NOAA SEAMAP monitoring program. The BONGO consists of two, parallel round frames (looking like a Bongo drum) to which nets with a 335 μm mesh size are attached, which is a good size to catch smaller, recently hatched larvae. The NEUSTON consists of a large rectangular frame to which a 950 μm (almost 1 millimeter!) mesh is attached. This net is specially designed to catch larger and older larvae, which occur right at the ocean surface. The third net type is a simple RING net equipped with a 1 mm mesh. Along the with BONGO, the RING net samples the whole water column from the surface to close to the bottom.  Dr. Simon Geist concentrates a net tow sample in the wet lab Dr. Simon Geist concentrates a net tow sample in the wet lab The fourth net type is the most sophisticated one: the MOCNESS has a rectangular frame to which 10 nets of 333 μm mesh are attached, which are opened and closed one at a time. This allows us to target different discrete depths to detect if zooplankton and fish larvae are aggregating in a certain depth layers of the water column. It is important to get as close to the bottom, since some zooplankton and fish larvae may hide out very close to it during the day. We have an online depth sensor attached when these nets are deployed, which allows us to get very close to the bottom (within 2 m) without running the net aground, which would result in the damage or loss. Fingers crossed, but so far we have not lost any gear during the October and the January cruise. After a net is successfully recovered, the mesh needs to be rinsed down carefully to collect organisms that are sticking to the mesh into the so-called “cod end” or net bucket. We then gently transfer what we’ve collected into a sample jar, to which either pure ethanol or formalin solution as fixatives are added to preserve the organisms. We have encountered a nice variety of larval and juvenile fish so far, which will be identified back home in the lab. However, we are curious to hear your thoughts about which species are shown in the 13 images provided here. Let us know in the comments, on our Facebook site or via email to [email protected]! All in all, we keep ourselves busy during the days at sea and everybody is quite tired when going to bed in the evening. The constant rolling of the boat does its part as well, but we were lucky that the sea was not as rough as one could imagine for being the middle of winter. Over time, working on a research vessel can be quite exhausting and I think each of us is happy to have a holiday on Monday to recover. We are all really impressed how smoothly both of our cruises have gone. The atmosphere onboard both the R/V Point Sur and the Pelican have been fantastic, and I consider myself very lucky that our team consists of enthusiastic researchers and crew who get along with each other, especially considering that we’re all cramped together on a small vessel for a week.

So long, we are off to knock the last stations out for this cruise! After that, we will return home to Corpus Christi and get some samples analyzed until we come back for our third and last cruise of this project in March! The RAPID Plankton team is out at sea again! Led by Chief Scientist Dr. Beth Stauffer, the plankton researchers from the Robinson and Stauffer Lab‘s at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette departed from the LUMCON dock at Cocodrie, LA Saturday afternoon on the R/V Pelican...

Read more on Dr. Robinson's blog ! The cruise is over, but we asked two of our undergraduate researchers (and first-time cruisers), Cristian Camacho and Valeria Nuñez, to share their experiences! As two undergraduates at Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi (TAMUCC), the opportunity to be a part of a research cruise in the Gulf of Mexico wasn’t something we thought would cross our paths until we were given the chance by our research professor, Dr. Simon Geist. Working in Dr. Geist’s Early Life History Research Lab consists of helping with the work that is shaped into the current research projects of his graduate students. We were presented with this rare opportunity that not many undergraduates are given and these are our experiences: Valeria: Being a marine biology major, I’ve heard of all sorts of reactions from friends and family about the choice of my degree. The reactions range from surprise and doubt about job security, curiosity as to what kind of work that entails, and even praise for trying to save the planet. With all these reactions, I stayed strong with my decision, and the experience of being a part of this research cruise has even solidified it. Being surrounded by skilled scientists was a little intimidating at first, but they all made me feel so welcome and they all contributed to helping learn along the way. I learned many things I could have only learned while being in the field, including making some mistakes along the way. The tasks that were given to me at hand challenged me, and being able to handle them made me feel much more confident as a student scientist. I saw many zooplankton species that I hadn’t seen before, including a lobster and a squid! I hadn’t encountered many of the species we caught so it was neat to see them in our nets. Overall, I am very grateful and happy to have been given the chance to be on this research cruise, and I will carry my experience forward to many more scientific opportunities that come my way.

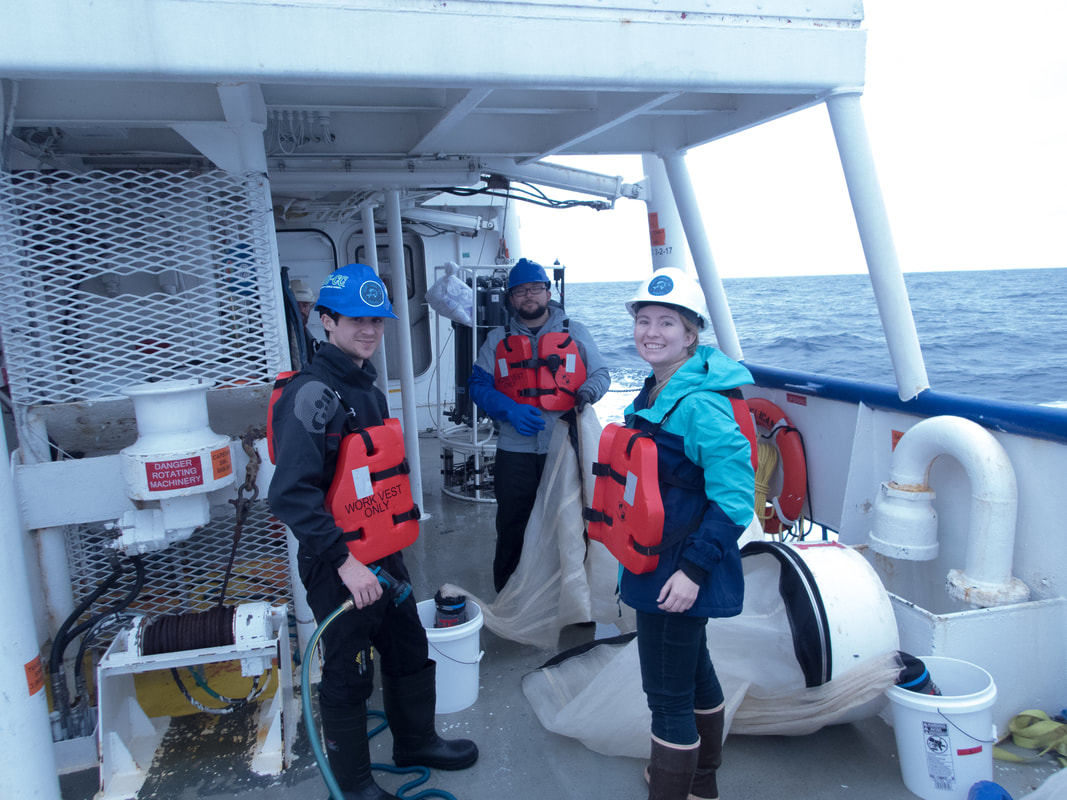

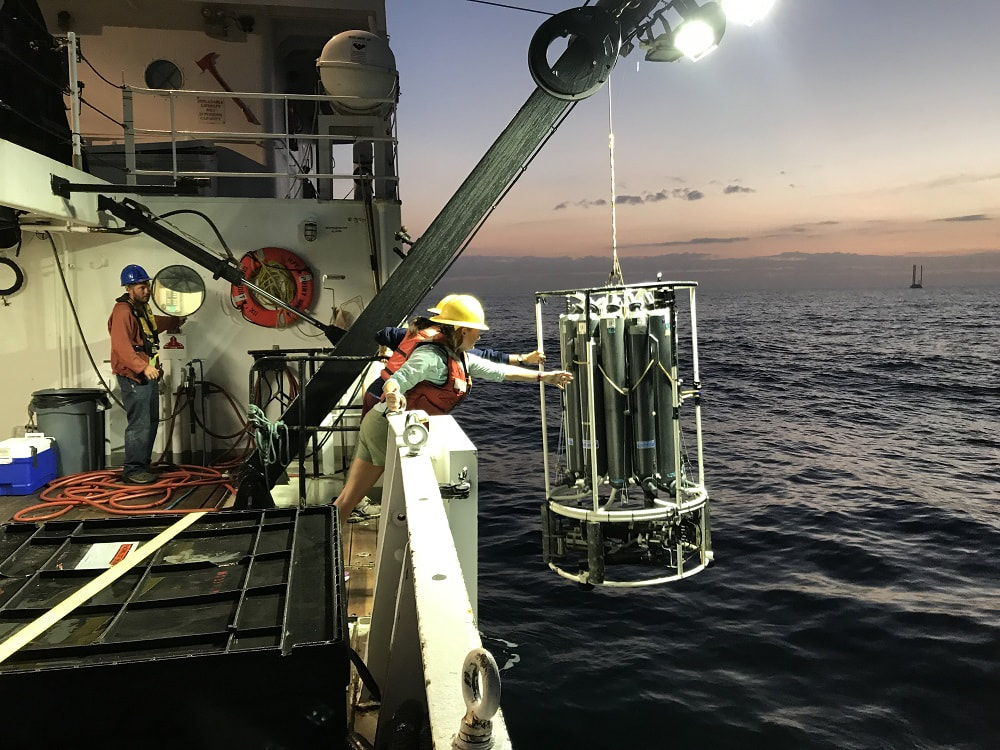

Cristian: Back in Corpus Christi, I am known as the friend who wants to travel to visit all the national parks in the US and to experience more of the world. I’ve always spoken about visiting the west coast states or revisiting Europe to see my birth country, Germany, and the surrounding countries. I never thought to venture out into the deep blue sea. I was excited, to say the least, when Dr. Geist asked me if I would like to be part of the research team on the RAPID Plankton cruise. It was one of the most eye-opening research experiences yet! I made new friends, learned how to tame the MOCNESS, and saw many new kinds of plankton, including copepods in the family Sapphirinidae! When I first thought about becoming a marine biologist I never knew what I would like to concentrate on because the ocean has such a vast biodiversity of marine life. Being exposed to new labs and seeing what they research was a learning experience on its own. I had the chance to learn about the most abundant predators of the ocean, nanoflagellates, and I was able to see the beautiful colors of live ctenophores. This research opportunity was more than an offshore experience. It made me feel like I was truly a scientist.  An example of some of the phytoplankton found in the ocean, image credit unknown An example of some of the phytoplankton found in the ocean, image credit unknown Posted by Beth Stauffer, Assistant Professor of Biology, UL Lafayette Our cruise is focused on plankton in the Gulf of Mexico, but this term really describes a lifestyle of “wandering” or “going with the flow” of the currents more than a group of organisms. Gabrielle Corradino, a PhD student with Dr. Astrid Schnetzer at NC State University, and I are studying the tiniest of these - and the ones at the base of the food web - on this cruise. Much like plants on land, microscopic phytoplankton are the photosynthetic members that use light and carbon dioxide to produce carbohydrates (or sugars) and oxygen. They do this really well: more than 50% of the oxygen on our planet is produced by phytoplankton in the ocean! This primary production also makes phytoplankton the base of the marine food web. Zooplankton, fish, even large animals like dolphins and whales, rely on these food webs! Our project is specifically focused on understanding the effects of Hurricane Harvey and its floodwaters on planktonic food webs in the Gulf. Therefore, we have to quantify who is there, since different species of phytoplankton can support different consumers. The main instrument we use to do this is the CTD (conductivity-temperature-depth), which is a suite of sensors mounted to a cage that is lowered over the side of the ship. The cage also holds bottles which can be triggered to collect water at specific depths. We collect water from these bottles for analyses back in the lab using microscopes, a flow cytometer (to look at the really small stuff), and based on their DNA, which can tell us what’s there without us even seeing it. Check out Gabrielle’s Instagram (@marchoftheplankton) to see this instrument in action! We are also running experiments while on the ship to measure how much consumption is going on by two different groups of zooplankton: small single-called microzooplankton that can grow almost as fast as their prey, and larger copepods that you might recognize from Sponge Bob Square Pants! These experiments are done in bottles in a tub on the back deck that has seawater running through it. We try to mimic the natural ocean as much as possible for the 24 hours we let those food webs function. We were lucky to have been out here in late July sampling plankton as part of the NOAA-supported Gulf of Mexico Ecosystems and Carbon Cruise (GOMECC3). This was about a month before Harvey hit the Texas coast. The data we’re collecting on this cruise will help us see how who is there and what they’re doing has changed after such a massive pulse of freshwater was delivered to the system. It will also tie into the rest of our group’s work on larger zooplankton and the complex food webs that are supported by the tiny phytoplankton.  Valeria and Cristian help collect samples from one of the MOCNESS nets (photo by Kate Thompson) Valeria and Cristian help collect samples from one of the MOCNESS nets (photo by Kate Thompson) Posted by Zach Topor, PhD student in Dr. Kelly Robinson's Lab Just like most people, Monday ushered in the start of our work week. However, rather than scooting a chair up to our desks or classrooms, we began our exploration of the ocean blue. A 05:30 wake up is early, even for morning people. But the anticipation of Station 1 motivated me and I sprung (dragged) myself out of bed for breakfast. With full bellies, a beautiful sunrise on the water (my favorite thing), and lots of optimism, our team started the day. We are out in the Gulf of Mexico, off the coast of Texas to see how flood waters from Hurricane Harvey have affected plankton communities, near- and offshore. Plankton, though tiny, have a great impact on all the food webs in the ocean. Everything starts with (or in) the plankton. And that makes it really exciting to study. This cruise is especially important to me because the data and samples that we collect will be contributing to my dissertation research on plankton community ecology. Station 1 marked the beginning of our sampling journey. On this cruise, we are deploying three types of nets to collect zooplankton at each station. Zooplankton are little animals and larvae in the ocean, drifting along in the currents. These include things like krill and copepods, fish larvae, and jellyfish. The net that collects the majority of my samples is called the Multiple Opening/Closing Net and Environmental Sensing System or MOCNESS for short. This system has ten (!) nets with remote controlled openings so that we can discretely sample zooplankton at different depths, all during one tow. With each net, we get a snapshot of the zooplankton community from that specific depth. I am really excited to find out what is happening down there. Even with a few procedural hiccups and some temperamental machinery (all expected on the first day), day 1 was a great success. Day 2 went smoothly (even if the seas weren’t) and our team worked really well together. So far we’ve had beautiful weather, cooperative seas, and a great team effort (not to mention, lots of plankton!!!). And I, for one, am looking forward to the sunrise tomorrow.

Posted by Beth Stauffer, 29 October 2017 In late August, Hurricane Harvey delivered a massive amount of devastating rainfall to Houston and surrounding areas. This water – 33 trillion gallons in total and 24.5 trillion gallons in southeast Texas and southern Louisiana – had to go somewhere. Much of it has been draining into the northwest Gulf of Mexico since then, during a time of year when such freshwater inputs to this system are not typical. Our collaborative team is heading out to this area to study the effects of all this freshwater on plankton in these waters. We are building on data collected just a month before the storm as well as historical datasets from the area to understand how the base of the Gulf of Mexico food web has been affected. Our team consists of members from four research groups based out of three institutions. We are steaming west towards our first station today in relatively comfortable conditions! We will be sampling intensively this coming week, and we will also continue to follow this system in the coming months. Overall, this research will help us build a better understanding of how historic storms like Harvey change our coastal oceans. A bit more about our collaborative team:

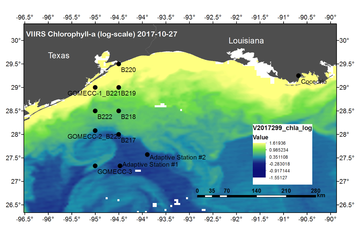

Dr. Kelly Robinson is an Assistant Professor of Biology at University of Louisiana at Lafayette. She is a biological oceanographer with expertise in zooplankton, particularly jellyfish. She is interested in understanding how climate change affects what animals are in the plankton and what that means for marine food webs both now and in the future. Zach Topor, a PhD student in the Robinson Lab, is interested in community ecology, especially in the plankton. This is his second oceanographic cruise, and he’s looking forward to 7 to 11 foot seas and seeing the Gulf of Mexico for the first time. Kate Thompson is an undergraduate student researcher. She has a passion for neuroscience and is planning to pursue that in graduate school. This is her first cruise, and she’s hoping to see whales. Dr. Beth Stauffer is an Assistant Professor of Biology at UL Lafayette. She studies the tiny plant-like organisms at the base of marine food webs – phytoplankton – and tries to understand how changes in the species that are present affect the larger animals that depend upon these food webs. Her Masters student Mrun Pathare was part of the GOMECC team that sampled this area in late July, so we're looking forward to seeing how a little time and a lot of freshwater can change things. Gabrielle Corradino is a PhD student working with Dr. Astrid Schnetzer, an Associate Professor of Marine, Earth, & Atmospheric Sciences at NC State University. Dr. Schnetzer’s research focuses on protists (single-called producers and consumers) and zooplankton (primarily copepods and euphausiids), and how natural and man-made processed shape communities and functions of these important organisms. Gabrielle is researching the understudied nanoflagellates as part of her dissertation. She was also part of the GOMECC team who collected samples and ran experiments in these Gulf waters prior to Harvey, and she’s interested to see how the plankton communities have shifted since then. Dr. Simon Geist is an Assistant Professor in Life Sciences at Texas A&M Corpus Christi. His research focuses on ecology, ecophysiology, and interactions of zooplankton with the environment. He’s excited to be doing our first cruise for this project. Dr. Geist has collaborated with the NOAA Southeast Area Monitoring and Assessment Program (SEAMAP) program, an ongoing study on zooplankton abundances that will provide historical context for our findings. Valeria Nuñez is an undergraduate student researcher finishing up her last semester of studies! She wants to combine her love of SCUBA diving, conservation, and education in her future career. This is her first cruise. Cristian Camacho is an undergraduate student researcher. He will be graduating in May, and hopes to get out of Texas for grad school. This is his first cruise, and he’s looking forward to experiencing the offshore life (high seas and all!).  Satellite image of surface chlorophyll in our RAPID study region Satellite image of surface chlorophyll in our RAPID study region The Stauffer Lab is getting ready to head out on the R/V Point Sur on the first of three cruises studying effects of Hurricane Harvey on plankton communities and food webs in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Stay tuned to this page for cruise updates from our collaborative RAPID research team!  Mrun (R) and Gabrielle (L) getting ready for the GOMECC-3 cruise in Key West Mrun (R) and Gabrielle (L) getting ready for the GOMECC-3 cruise in Key West Masters student Mrunmayee Pathare is on a 35-day research cruise aboard the NOAA R/V Ronald H. Brown. In collaboration with our colleagues Dr. Astrid Schnetzer and Ph.D. student Gabrielle Corradino at NC State University, Mrun is quantifying feeding on phytoplankton communities in the Gulf of Mexico. She recently contributed a post to the GOMECC-3 cruise blog, check it out!  Jaylyn Babitch is a Masters student in the Stauffer Lab. She recently spent a week in central CA with our collaborators in the Alliance for Coastal Technologies as they tested multi-spectral fluorometers that can distinguish among different classes of phytoplankton, including groups that cause harmful algal blooms (HABs). Here she shares some of her experiences in the field. With colleagues from Moss Landing Marine Lab, UC Santa Cruz, and University of Michigan, we did a one-day cruise throughout Monterey Bay aboard the R/V Martin, stopping at 7 stations to assess the performance of 5 new fluorometers under a variety of estuarine to marine conditions. This cruise was part of a technology validation exercised led by ACT to document performance of these new sensors against reference methods.

A lot of times, field work = tapping into your best MacGyver skills. This was our very high-tech (or rather ingenious) garbage can flow-through system, which allowed the fluorometers to all be exposed to the same water parcel, and therefore the same abiotic conditions and phytoplankton assemblages, at the same time during each station stop. These sorts of considerations are part of what makes the ACT team a top notch testing group! Additional field tests are being done throughout the rest of the summer in freshwater and estuarine conditions with very different phytoplankton assemblages. Stay tuned to the ACT website for more info on test results for each fluorometer and for more information on technologies for hunting HABs across aquatic environments.

|

AuthorsMembers of the Stauffer Lab in the Dept. of Biology at UL Lafayette. Check out the byline for specific blog post author information! Archives

March 2018

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed